The use of ethnographical methods in design research here and there out of academic circles brings back the question of the role of "theory", and its articulation with research methodologies and techniques. This is a recurring topic with clients, research colleagues and I've seen it popping on mailing lists such as anthrodesign.

The use of ethnographical methods in design research here and there out of academic circles brings back the question of the role of "theory", and its articulation with research methodologies and techniques. This is a recurring topic with clients, research colleagues and I've seen it popping on mailing lists such as anthrodesign.

Before jumping to the differentiation between theory and methodologies, it's important to acknowledge that there is no just "one" ethnography. The use of this term, especially in business circles, is not fair. It's as if it is was a general container to provide engineers/strategists/designers with a one-way solution for their problem at hand. An article such as "fieldwork and ethnography: a perspective from CSCW" by Harper et al. (to be found in the EPIC 2005 proceedings) gives an introduction to some of them.

"Part of the trouble has to do with the fact that the word ethnography can be used somewhat capriciously for a whole range of purposes; as a label used by some for practices to be jealously defended; a label used to give renewed vigor, even fashionability for an old trade, fieldwork; and at other times a label used to defend pointless hanging around. What ethnography is, though it clearly has some kind of character, is not at all clear"

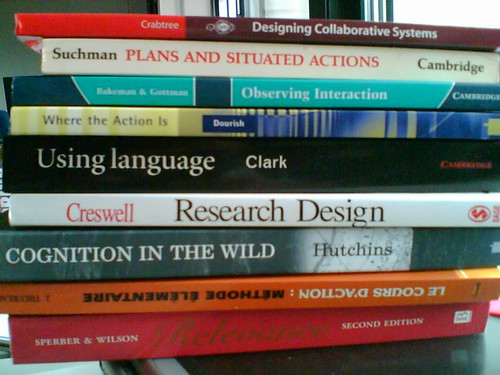

The paper basically shows that there are different distinction based on disciplinary assumptions about methods, theories and sensibilities. The authors picked up 4 texts (Cognitive Work Analysis by Vicente, Contextual Inquiry by Beyer and Holzblatt, Designing Collaborative Systems by Crabtree, and Marcus' Ethnography through Thick and Thin) and show how they represent different viewpoints: a ‘cognitive science’ viewpoint; a ‘practical’ approach; an ethnomethodological perspective, and a postmodern alternative. They show how that each of them reflects different orientations and sensibilities and not only refer to which methods to choose and how to look at "data". The paper also suggests to use the term "field work" instead than "ethnography" since the former is better suited to the activity carried out in design research.

Who are the protagonists at stake here? Let's say that we can distinguish 3 components:

- Theories of science analyze the condition of production of knowledge from a philosophical viewpoint. Example: positivist view (authentic knowledge is that based on actual sense experience), more critical approach

- Methodologies describe the general ways about how to carry out research. Based on considerations emerging from theories, methodologies propose a set of methods. Example: qualitative analysis, quantitative analysis

- Methods that are general ways to study a class of phenomena, based on theoretical tools (how about how articulate data and theories) and techniques (recipes to acquire, transform, analyze data).

. Then, there are finer-scaled theories that act as subset of the general theories of science: Chomsky's Generative Grammar, Sperber's relevance theory of human communication, Suchman's Situated Action theory, Media theory about framing, etc.

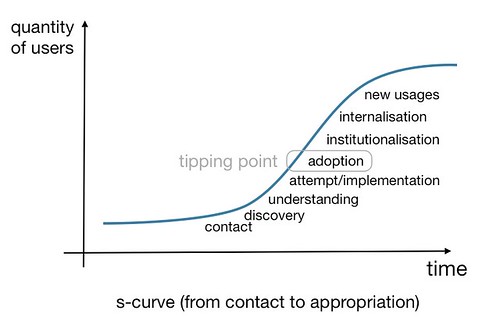

In the context of design research, the situation is a bit more specific given that it corresponds to (1) a qualitative and, generally, (2) an inductive model of research. It's qualitative as it tries to uncover cases that can be selected according to whether they typify (or not), specific characteristics or contextual locations. It's also generally inductive because general principles (yes, theories) can be developed from specific observations (as opposed to other forms of research which are based on hypothesis-testing). I tried to list the link between empirical research and theories in this context:

- Certain theories can frame the research and give an idea of what one is trying to achieve and look for. Or, as formulated by Harper et al.:"disciplinary ‘sensibilities’ may allow us to produce a set of broad, ‘sensitising’ or ‘illuminating’ concepts, starting points that can serve as reminders that some kinds of thing are often to be found whilst not diverting us from our equally powerful interest in what is uniquely ‘situated’ about what we are studying. In short, provide us with a ‘way of looking’". What it means is that it allows to efficiently synthesize, interpret and sort out insights. In sum, it orients the research.

- The goal of this research is to generate a theory, Beyond describing and exploring the context at hand, it's also to articulate principles or more general notions or rules, and understand a culture based on certain aspects. To some extent, building a theory can be a research goal.

Of course, this is a quick summary and there is more to it. This is all and good but people interested by design research may want to know more about what theories or theoretical spin they might want to employ. Ranging from Ethnomethodology to Interactionism or Grounded Theory and Activity Theory, there is plenty of possibilities here and I won't enter into much details in this blogpost.

What is interesting is perhaps the discussion about which sort of theoretical twist are employed in "design research". In HCI and CSCW, which have a strong ethnographically-informed design approach, it seems that ethnomethodology is very common and french ergonomics is all about Activity Theory (and modified versions). Other approach this without any reference to theories, such as Jan Chipchase's work at Nokia Design which is fairly descriptive and exploratory. Again, as I stated above, there is no "one way" here, the important thing is to find the method the researcher is comfortable with in conjunction with he/she and the design team think is relevant for the time being. On my side, I do think that an approach such as "Grounded Theory" by Strauss and Corbin is pertinent and flexible enough for design research.

(

(

Taking some time reading about technological failures, I found this interesting reference by

Taking some time reading about technological failures, I found this interesting reference by

One of my favorite graphic novel series lately is "

One of my favorite graphic novel series lately is "