While being thrown around here and there, the term "digital folklore" is sometimes used beyond pop discussions about on-line cultures, reaching academic/art book status, and sometimes peer-reviewed articles. The book "Digital Folklore. To computer users, with love and respect" by Olia Lialina & Dragan Espenschied is a good example of a fascinating exploration of this topic.

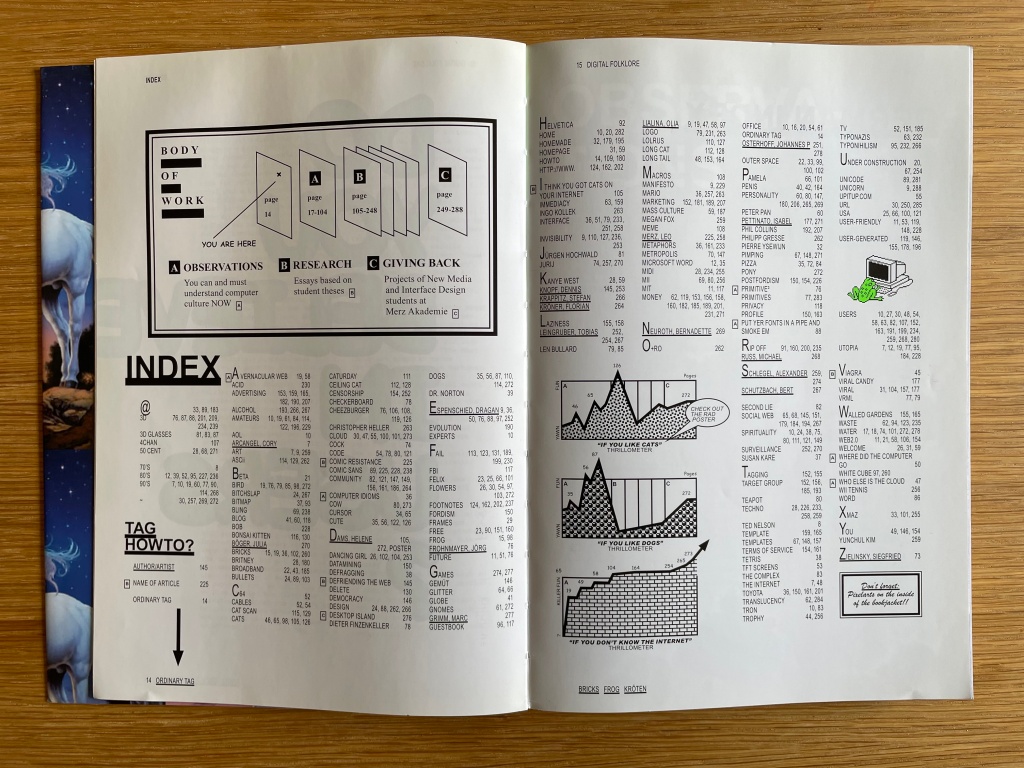

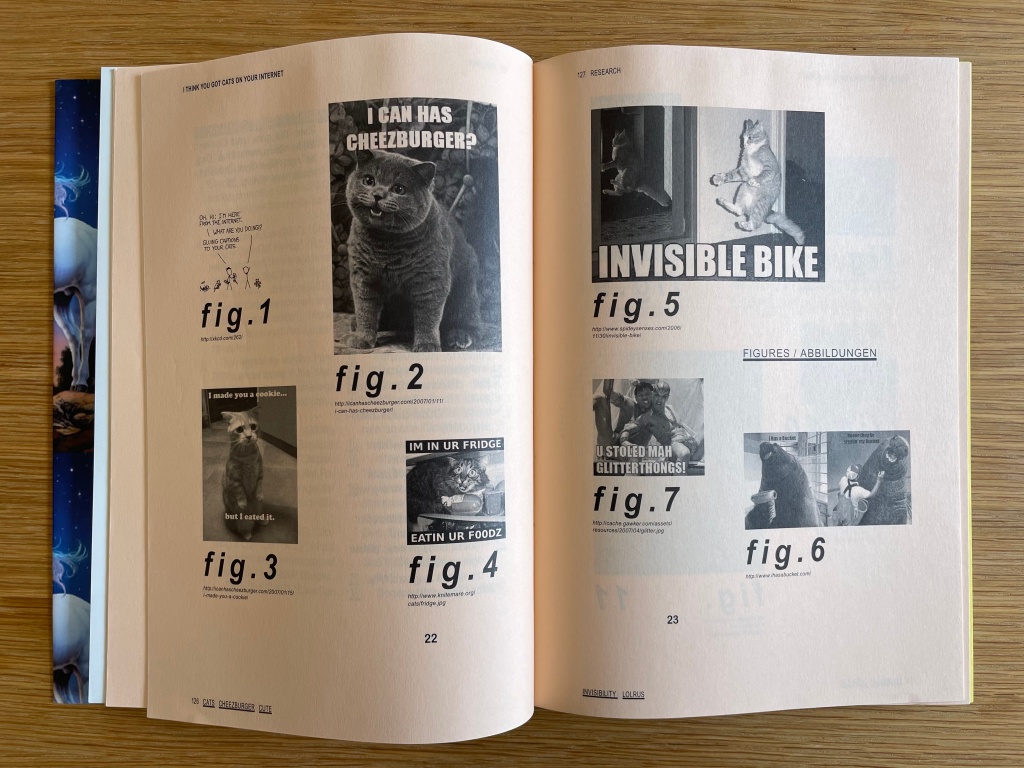

Published in 2009 by the Merz Akademie Hochschule für Gestaltung in Stuttgart, the book is an interesting collection of essays and art/design projects about one-line amateur cultures, DIY electronics, "dirtystyle", "typo-nihilism", memes as well as teapots or body parts extensions. Quite a wide array of topics, as attested by the index of the book, which works as a de facto table of content:

The authors' understanding of the term "digital folklore" in this book corresponds to the following definition:

"Digital folklore encompasses the customs, traditions and elements of visual, textual and audio culture that emerged from users' engagement with personal computer applications during the last decade of the 20th and the first decade of the 21th century."

While the aforementioned definition of "digital folklore" isn't the only one online (see for instance Gabriele de Seta's paper that I will get back to on another blogpost, or this podcast), I find it relevant that the most important aspect Lialina and Espenschied tackle in the book is this notion that "the domain of the digital must belong to people, not computers". The emphasis on users and their cultural obsessions, endeavors, pet peeves, aesthetics and odd interests is the angle with which they address the notion of "folklore"... which is a bit different than anthropological use of the term (even though there are obvious overlaps and crossovers). For them, it's about "believing in users".

Why do I blog this? Given that friends and colleagues have sometimes referred my interest and work as belonging to "digital folklore", I've always been intrigued by what it meant practically; and digging the various definition this term encompasses became relevant to me several years ago. I know the way they use the term generally corresponds to the academic field they come from, such as anthropology, history or philosophy and it made me realize that they sometimes negative connotations attached to the name "folklore" (or worse, to the adjective "folkloric") especially in French language can perhaps be circumvented.