My super quick notes from the Playful 2011 conference I attended in London last Friday. The main reason I enjoy going to Playful is that it always deal with peculiar aspects of playfulness and game-related technologies. It's more about the culture of play than the problem of the game industry. For instance, no one talked about the notion shown on the picture below, except to say that we need to move forward and talk about something else:

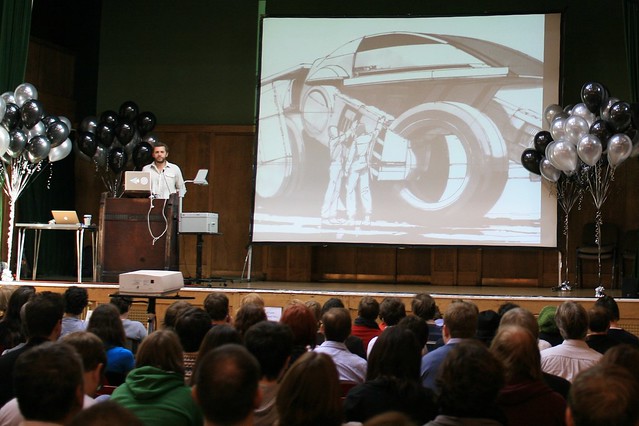

The topic this year was close to the one I handcrafted for the Lift09 conference (labelled "Where did the future go?"). The starting point of the conference was to consider the gap between the "future we were promised" (jetpacks, the Death star, AI, robots, big technological devices) and what currently have (the Hummer as opposed to a flying car, Siri instead of sentient robots). Some in the audience (or the twitterverse) noticed how this impression is a cultural construct:

"There was apparently a generation of British men seriously duped by science fiction a few decades ago and v disappointed now."

A big car from a sci-fi comic book, we don't have this kind of stuff today but we have Hummers

A big car from a sci-fi comic book, we don't have this kind of stuff today but we have Hummers

This gap is quite common in people interested in technology foresight or human-computer interaction. Researchers working on Ubiquitous Computing may be interesting in reading about this in a paper from Paul Dourish and Genevieve Bell entitled "Yesterday’s tomorrows: notes on ubiquitous computing’s dominant vision". In this article, the author describes how:

"the centrality of ubiquitous computing’s ‘‘proximate future’’ continually places its achievements out of reach, while simultaneously blinding us to current practice. By focusing on the future just around the corner, ubiquitous computing renders contemporary practice (at outside of research sites and ‘‘living labs’’), by definition, irrelevant or at the very least already outmoded. Arguably, though, ubiquitous computing is already here; it simply has not taken the form that we originally envisaged and continue to conjure in our visions of tomorrow."

... a lesson some speakers certainly followed during their speech, as they gave us some good insights about glimpses from unevenly distributed futures.

A quote from William "unevenly distributed futures" Gibson showed by Brendan Dawes that exemplifies this delusion

A quote from William "unevenly distributed futures" Gibson showed by Brendan Dawes that exemplifies this delusion

A side-effect of the aforementioned disappointment towards the "promises of the future" is the fact that human beings seem to be less prone to dealing with "big and futuristic projects". As Toby Barnes claimed, "there's not enough people trying to make a dent on the world", as exemplified by Neal Stephenson's recent comment about innovation starvation:

"Still, I worry that our inability to match the achievements of the 1960s space program might be symptomatic of a general failure of our society to get big things done. My parents and grandparents witnessed the creation of the airplane, the automobile, nuclear energy, and the computer to name only a few. Scientists and engineers who came of age during the first half of the 20th century could look forward to building things that would solve age-old problems, transform the landscape, build the economy, and provide jobs for the burgeoning middle class that was the basis for our stable democracy."

Although this delusion towards the future looks a bit sad, the talks were funny and engaging and I took plenty of notes... some might be loosely related to this topic but it's generally what happens in this kind of context.

In his talk called "Time Lords, frothing and Dungeon Maste", Matt Sheret relied on how his friends "play with cities" to highlight curious perspectives about the near future: role playing games, the Tower Bridge twitterbot and BERG London design projects. Above all, and because I knew the other projects, it's the perspective about RPG and the role of game masters that I quite enjoyed. He basically discussed how fictional cities in such games are somehow co-created by the players and the GM. The way dialogues between players and artifacts such as maps or urban descriptions can be seen as an interesting way to show how a "city talk to you".

A quote from Richard Lemarchand that I enjoyed: "people are not necessarily mean, they just want to see what happen if they try things out"... he showed how him and his fellow game designers noticed how playtesters were punching other people in their game... which led them to create characters that shake hands with players. Although this anecdote seems a bit futile, it's a good example of (1) the importance of playful interactions in games, (2) how you can rely on testing prototypes to tune a design proposition. It's always interesting to hear designers discussing how their understanding of player's psychology help them reconsider their work. This topic was also dealt with by Louise Downe in her talk about self-flushing toilets and automatic air-refreshener:

"I don't walk out toilets thinking it's OK, I need control over them. Intimacy with machines really requires trust. Trust that they think in the same way we do"

Chris O'Shea gave a quick overview of interesting toys and interactive projects for kids... based on some relevant data: how kids expect anything to be touchscreen (trying to zoom in), how "84% of parents are interested in asynchronous gaming to play collaboratively with their kids".

Also an important topic at Playful was the role of prototyping in the crafting of Playful experience. O'Shea showed how he used basic material (cardboard, plastic, lego bricks) to create iPhone casing and apps that can engage kids with basic activities:

This "low-fi prototyping" attitude was also exemplified by Brendan Dawes and Matt Ward, who gave a great presentation on designing peril, the fine line between entertainment, humor and fear. He showed how low-fi interaction is key to learn in a design research approach and that suspending people's disbelief is easier than they thought at first. (as shown in this video of their bomb project)

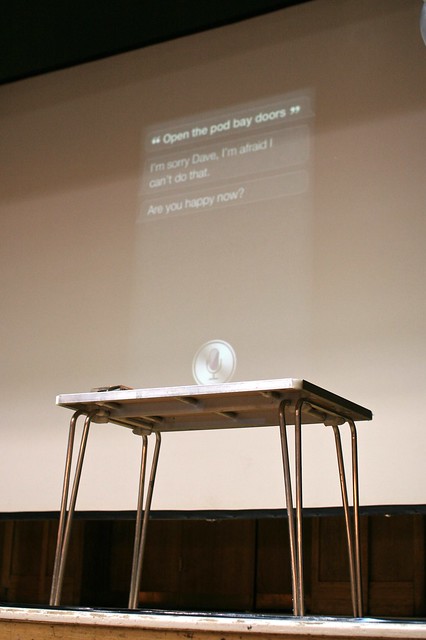

And finally, two highlights in terms of format. First Scribble Tennis was an entertaining idea: two players competing with drawings on an overhead projectors:  Second, a so-called artificial intelligence called Siri gave a talk on the stage table:

Second, a so-called artificial intelligence called Siri gave a talk on the stage table:  Well, actually, this didn't happen but this giant screenshot of the iOS-based personal assistant application next to a table (altar?) on stage gave me the impression that the future is not boring and brilliant.

Well, actually, this didn't happen but this giant screenshot of the iOS-based personal assistant application next to a table (altar?) on stage gave me the impression that the future is not boring and brilliant.