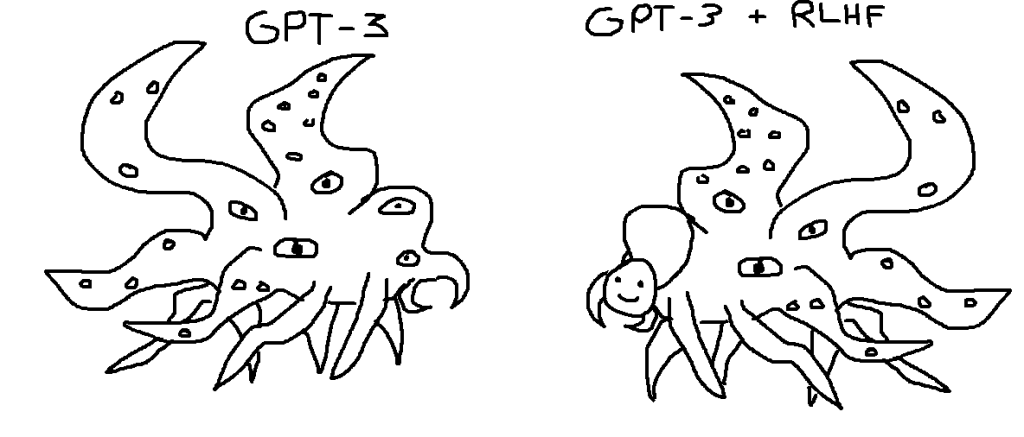

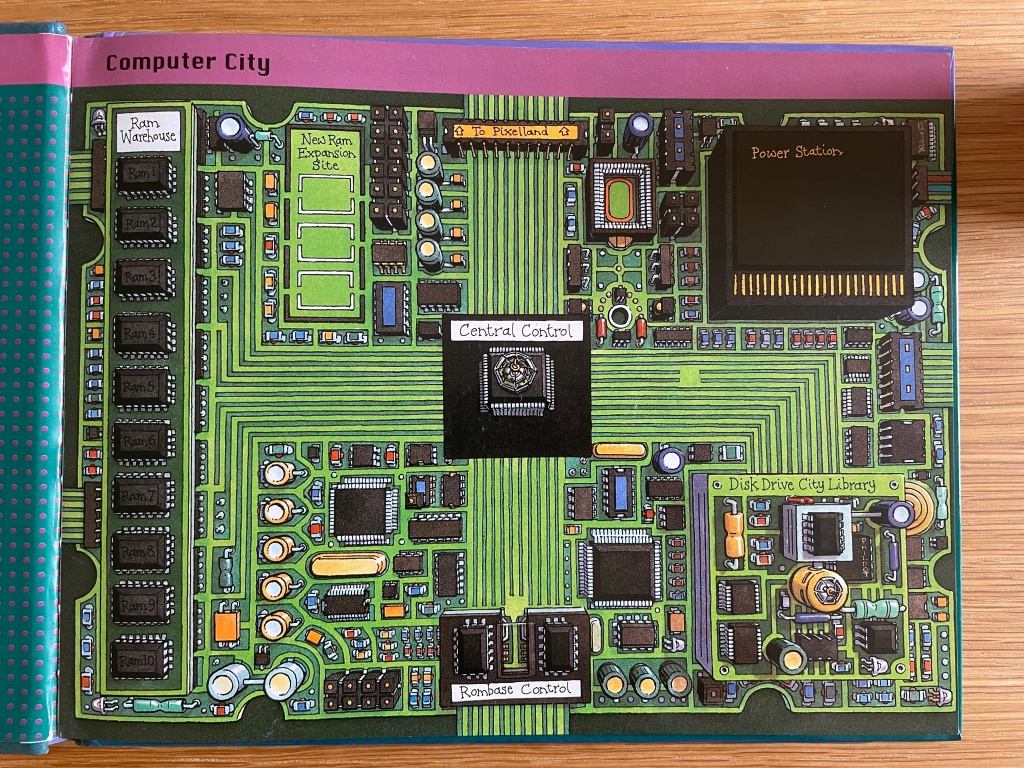

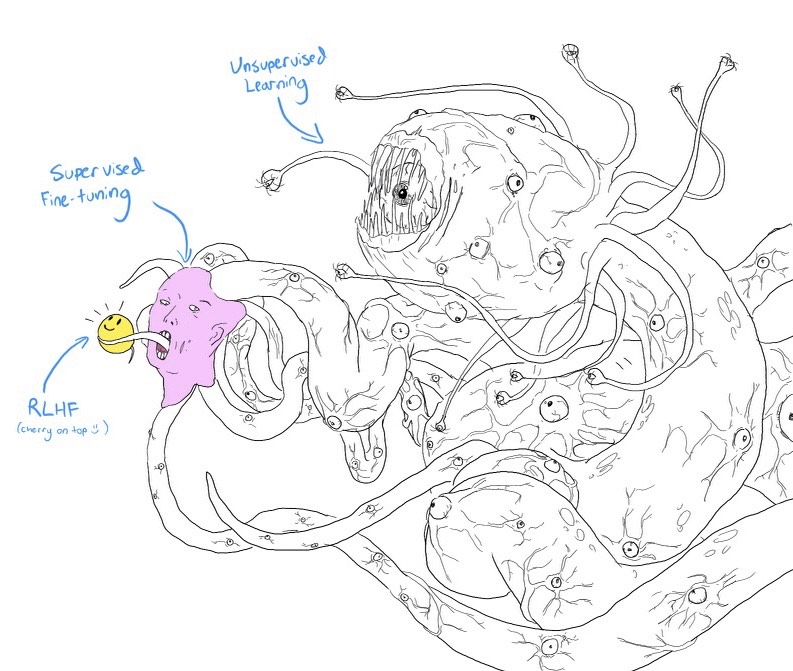

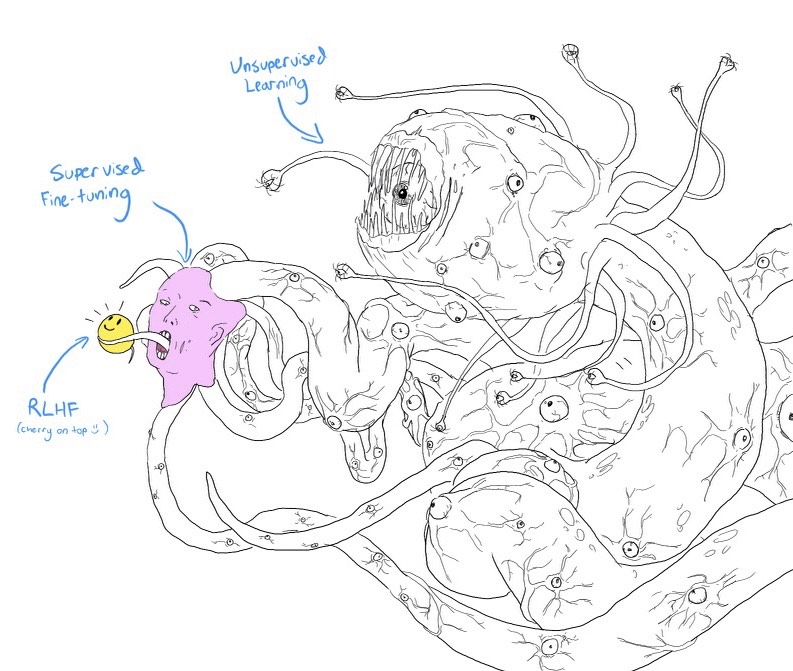

Chatting with Tommaso yesterday about the Machine Mirabilia project, he showed this uncanny representation of ChatGPT that made the round on social media a while back.

He then pointed me to a twitter thread from a technology researcher working in Machine Learning, which unpack the logic behind this monstrous representation. Some excerpts I captured :

First, some basics of how language models like ChatGPT work: Basically, the way you train a language model is by giving it insane quantities of text data and asking it over and over to predict what word comes next after a given passage. Eventually, it gets very good at this. This training is a type of unsupervised learning It's called that because the data (mountains of text scraped from the internet/books/etc) is just raw information—it hasn't been structured and labeled into nice input-output pairs (like, say, a database of images+labels). But it turns out models trained that way, by themselves, aren't all that useful. They can do some cool stuff, like generating a news article to match a lede. But they often find ways to generate plausible-seeming text completions that really weren't what you were going for. So researchers figured out some ways to make them work better. One basic trick is "fine-tuning": You partially retrain the model using data specifically for the task you care about. If you're training a customer service bot, for instance, then maybe you pay some human customer service agents to look at real customer questions and write examples of good responses. Then you use that nice clean dataset of question-response pairs to tweak the model.

Unlike the original training, this approach is "supervised" because the data you're using is structured as well-labeled input-output pairs. So you could also call it supervised fine-tuning. Another trick is called "reinforcement learning from human feedback," or RLHF. The way reinforcement learning usually works is that you tell an AI model to maximize some kind of score—like points in a video game—then let it figure out how to do that. RLHF is a bit trickier: How it works, very roughly, is that you give the model some prompts, let it generate a few possible completions, then ask a human to rank how good the different completions are. Then, you get your language model to try to learn how to predict the human's rankings… And then you do reinforcement learning on that, so the AI is trying to maximize how much the humans will like text it generates, based on what it learned about what humans like. So that's RLHF And now we can go back to the tentacle monster!

Now we know what all the words mean, the picture should make more sense. The idea is that even if we can build tools (like ChatGPT) that look helpful and friendly on the surface, that doesn't mean the system as a whole is like that. Instead……Maybe the bulk of what's going on is an inhuman Lovecraftian process that's totally alien to how we think about the world, even if it can present a nice face. (Note that it's not about the tentacle monster being evil or conscious—just that it could be very, very weird.)

See also this addition to her thread:

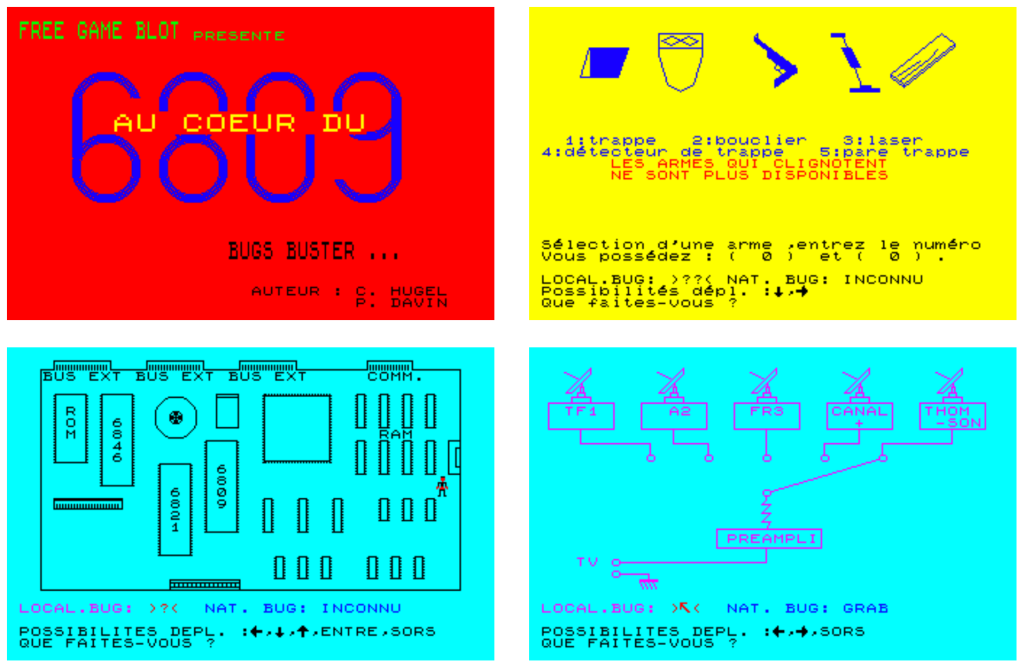

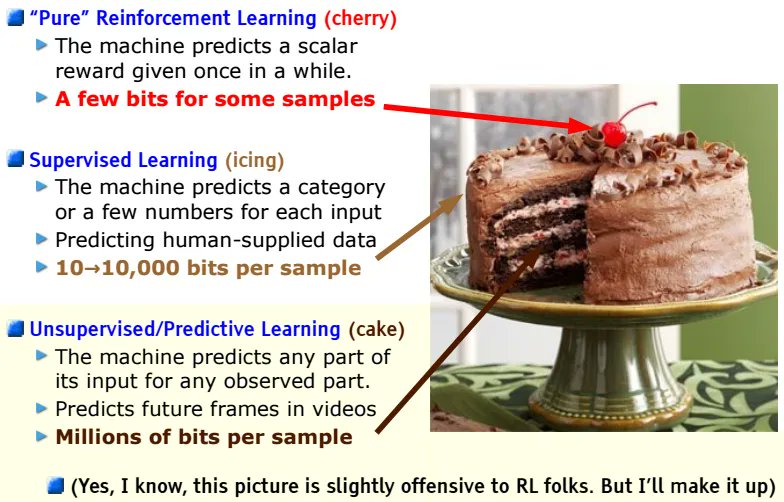

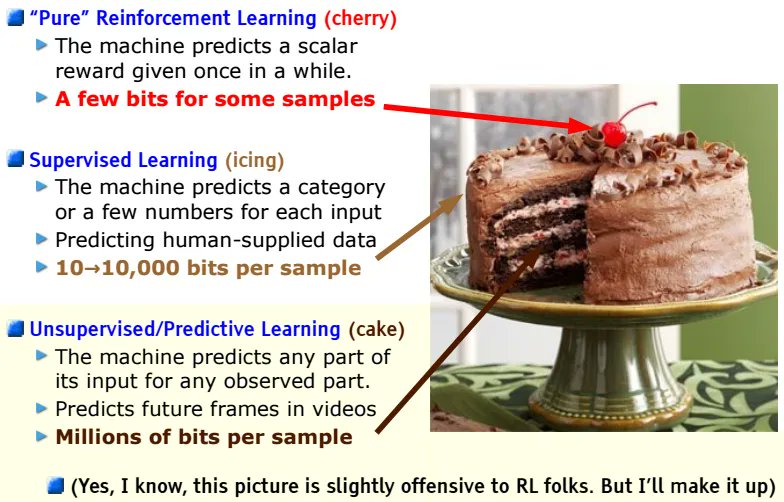

"But wait," I hear you say, "You promised cake!" You're right, I did. And here's why—because the tentacle monster is also a play on a very famous slide by a very famous researcher. Back in 2016, Yann LeCun (Chief AI Scientist at FB) presented this slide at NeurIPS, one of the biggest AI research conferences. Back then, there was a lot of excitement about RL as the key to intelligence, so LeCun was making a totally different point… …Namely, that RL was only the "cherry on top," whereas unsupervised learning was the bulk of how intelligence works. To an AI researcher, the labels on the tentacle monster immediately recall this cake, driven home by the cheery "cherry on top :)

Why do I blog this? This is an interesting example of how experts rely on fantastic creatures to make sense of technologies. This case is quite relevant as the "monster metaphor" is sometimes associated with laymen, or people who are clueless about the way these systems work (as in "naive physics" phenomena). The AI tentacle monster represented above, and how it circulated on social media, shows that it's not the case. And that such visuals/metaphor can be used to characterize what these entities are, as well as their moral connotations (as illustrated by the adjectives used by the author: "evil", "nice", "helpful", "friendly"). T