The game controller book project moves slowly but we tentatively wrote a draft of the book proposal that we intend to use. The provisional title is "The Joypad Continuum: tracing the evolution of game pad design" (by Nicolas Nova and Laurent Bolli).

The game controller book project moves slowly but we tentatively wrote a draft of the book proposal that we intend to use. The provisional title is "The Joypad Continuum: tracing the evolution of game pad design" (by Nicolas Nova and Laurent Bolli).

For the record, there's already some interest here and there but we thought it would be good to confront the book ideas with potential readers. The poster above is one of the artifacts that reflect the work we're doing to analyze the game pads. And yes it's a book entirely focused on joypads. Joysticks will be mentioned of course, but we zero in the evolution of pads.

Feel free to comment on this, we already collected lots of feedback, which is very refreshing and insightful (thanks for those who sent comments and emails). The outline is almost there and we have lots of material for the different parts of the book. We'll post stuff later on.

Project description

This book describes the evolution of joypad designs over the short history of video games. It systematically tracks the process of change and how it happened in order to reach two goals. On the one hand, the book sets off to discuss the design decisions behind key interface attributes featured by this apparently banal class of artifact. It primarily focuses on joypad shapes, direction and action buttons as well as various other features that have enriched video game controllers. On the other hand, the book discusses the circulation and modification of such design attributes over time and between joypad models. Doing so, this work exemplifies general principles about patterns of change and highlights the specificities of this class of technical objects.

Among contemporary objects, joypads are peculiar given their existence both as physical artifacts and as interfaces to control characters in digital environments. Unlike joysticks, they correspond to a type of game controller held in the hand where fingers interact with buttons, sliders and tiny sticks. Therefore, observing this unique device enables to highlight critical implications about human-computer interaction and innovation in the field of new media: the intricate relationship between joypads and video game design, the evolution of game interfaces (and upcoming changes) as well as the evolution of technical objects in general.

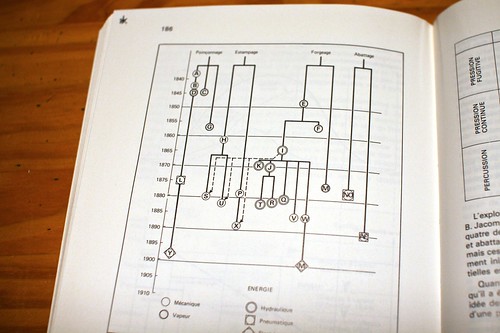

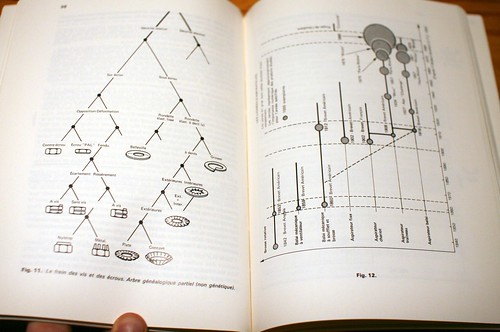

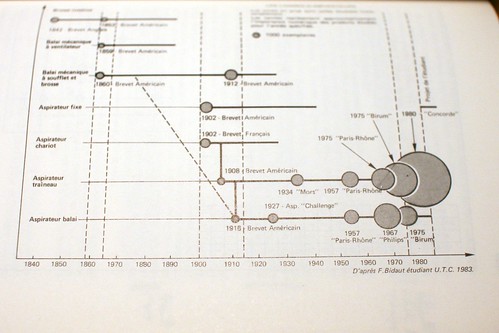

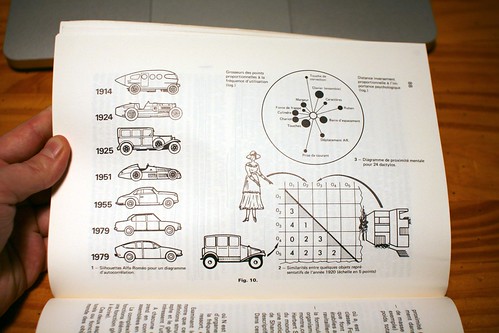

In terms of theoretical framework, the book adopts an evolutionary perspective (Simondon, 1980; Deforge, 1985; Basalla, 1988) to describe the different paths taken by joypad design and to give the reader a critical overview of the underlying trends that shaped the various iterations of this artifact. However, the evolutionary analogy serves here as an organizing principles to track the iterative changes of objects and does not reflect any teleological assumption of progress. From a methodological perspective, this book is based on the ethnographical analysis of technical objects (Star, 1999), interviews with controller designers or the gathering of second-hand material about the design decisions that led to certain joypads (interviews, books, patents). Instead of adopting the common approach focused on studying usage and people, this work is based on the examination of artifacts. The systematic analysis of artifactual iterations enabled to build genealogies and to foster insights about patterns of changes (e.g. evolution of the number of buttons, evolution of the button/surface ratio). Furthermore, the evolutionary angle posits that objects are not explored independently but as being part of various lineages, which shares common design attributes such as controller shapes or navigation interface.

Such book targets mainly academic researchers in the field of Science and Technology Studies, New Media or Human-Computer Interaction as well as practitioners in the field of interaction design. However, the book is also meant to be relevant for video game fans who are interested in a deeper perspective about game controllers. It is intended to be short (140-180 pages) and illustrated by black and white joypad drawings and diagrams (genealogy trees, histograms as carried out by Deforge, 1985).

Fields of discourse:

The fields of discourse adopted in this project are a combination of:

- Science and technology studies (Simondon, 1980; Basalla, 1988; Akrich, 1992) for the analysis of technical objects and the description about how mundane artifacts are the product of various forces. More specifically, the work of Zimmermann (2010) about the circulation of cultural elements is informative for the analysis of how design choices about game pads spread and evolve. The book also relies on the work of Star (1999) concerning how ethnography can be applied to physical artifacts.

- Human-Computer Interaction (Gibson, 1977; Norman, 1990; Gaver, 1991; Gaver, 1996) for the focus on interfaces and the notion of affordance. At first this term corresponded to the action possibilities present in the environment. This notion evolved in the field of HCI to refer to "the perceived and actual properties of the thing, primarily those fundamental properties that determine just how the thing could possibly be used." (Norman, 1990).

- New media studies and more specifically Platform Studies (Monfort and Bogost, 2009) because of the renewal of interest in platforms/technical objects.

Reasons for writing this book:

The first reason to write this book stemmed from the personal collection of joypad we collected in the previous months. This material enabled to analyze and discuss the evolution of these technical objects and serve as the starting point for interaction and game design research in different contexts (workshops with students, seminar with practitioners).

A second reason is that the large majority of books about game interfaces are non-academic and take a descriptive approach with plenty of pictures but a limited analysis of their evolution (see for example Forster, W. and Freundorfer, S., 2003 or Miller et al., 2009). Our interested lies in providing an analytical perspective about joypads instead of a description of all the existing artifacts.

In addition, there is currently a renewed interest in studying artifacts (beyond their usage) in new media studies, as attested by the Platform Studies collection at the MIT press. We therefore believe the analysis of joypads is relevant both from the video game analysis standpoint and also as an introduction to the analysis of technical objects. Compared to other research foci (such as video game analysis or media usage), the joypad is a less-explored element that is paradoxical compared to its iconic nature as a powerful metaphor for video games. Because of the potential appeal of joypad to readers, the book is also an opportunity to exemplify general lessons about the history of technical objects (which generally draws upon artifacts that are less common for todays' readers such as washing machines or car engines).

Finally, from a video game standpoint, looking back at the evolution of game controllers is important given that the console manufacturers are transferring hardware cycle to the peripherals rather than console platforms. Furthermore, the disappearance of the controller in Microsoft Natal's project and its recombination in the case of the Wii and Sony's Motion Controller makes the joypad an interesting object to investigate.

References:

Akrich, M. (1992), "The description of technical objects", in Bijker, W.E., Law, J. (Eds),Shaping Technology/Building Society, MIT Press, Cambridge, MA, pp.205-24.

Basalla, G. (1988). The Evolution of Technology. Cambridge University Press.

Deforge, Y. (1985). Technologie et génétique de l'objet industriel. Paris: Maloine.

Forster, W. and Freundorfer, S. (2003). Joysticks. Gameplan; Auflage.

Gaver, W. (1996). Affordances for interaction: The social is material for design. Ecological Psychology, 8(2).

Gaver, W. (1991). Technology affordances. Proceedings of CHI, 1991 (New Orleans, Lousiana, USA, April 28 - May 2, 1991) ACM, New York.

Miller, F., Vandome, A.F., McBrewster, J. (2009). Game Controller. Alphascript Publishing.

Montfort, N. & Bogost, I. (2009). Racing the Beam The Atari Video Computer System. MIT press.

Norman, D. A. (1990). The design of everyday things. New York: Doubleday.

Simondon, G. (1980), trans. Ninian Mellamphy, On the Mode of Existence of Technical Objects. London: University of Western Ontario, 1980 [1958].

Star, S.L. (1999). “The Ethnography of Infrastructure,” American Behavioral . Scientist, 43: 377-391

Tulathimutte, T. (2005). Controller Mediation in Human-Computer Play. Honors Thesis, Stanford University.

Zimmermann, B. (2010). Redesigning Culture: Chinese Characters in Alphabet-Encoded Networks, Design and Culture, Berg Publishers.

Just saw this intriguing link called "5 Digital Trends Shaping the Consumer Experience" sent by @iamdanw and I found it fascinating.

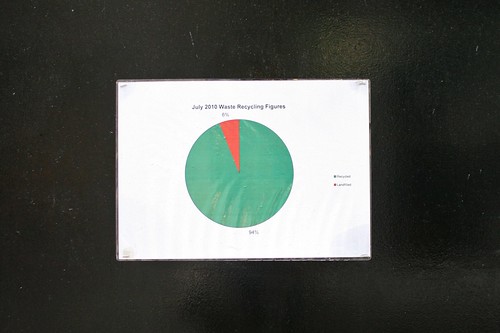

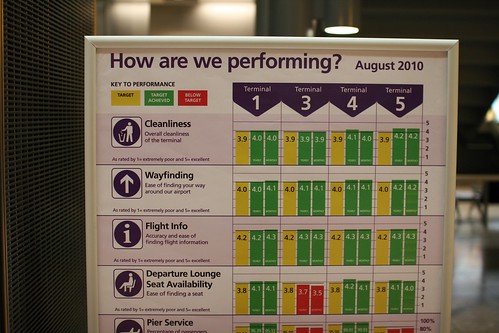

Just saw this intriguing link called "5 Digital Trends Shaping the Consumer Experience" sent by @iamdanw and I found it fascinating.  There seems to be growing and conspicuous increase of feedback indicator in public space, based (or not) on PPT metaphor. Seen in London last week.

There seems to be growing and conspicuous increase of feedback indicator in public space, based (or not) on PPT metaphor. Seen in London last week.

"

"

As part of our

As part of our